When the boys and girls went off to war in the 1940s to fight and die in WWII or to do the same in the 1950s during the Korean Conflict or the many “Operation” names of battles in Iraq and Afghanistan, they were thanked and applauded for their service. But one war stands out as the one where military veterans were not applauded or feted or thanked.

Still, some, like other boys and girls who went to war, died. In fact, 58, 315 names of those who died during the Vietnam war, including about 1,200 who are still listed as MIA — Missing in Action — and eight women are etched into the basalt-like material of the wall.

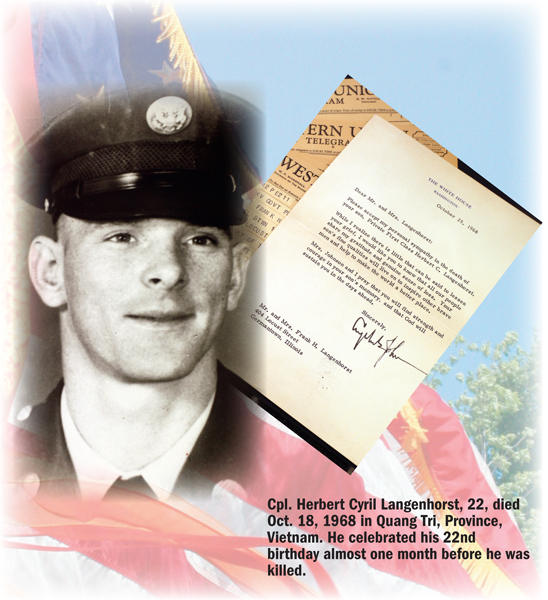

Among those names is that of Cpl. Herbert Cyril Langenhorst, a young man from Germantown who died in Quang Tri Province on Oct. 18, 1968.

Herbie, as his brothers and sisters, mom and dad called him, was the 11th of 13 living children who farmed a short distance from Germantown and who belonged to St. Boniface Parish.

Three of the Langenhorst brothers and their sister, Darlene, talked about life as part of a family of 13 children and what kind of a boy Herbie had been.

Working on the farm was hard, brother Joe said. They farmed and raised livestock of all kinds. Brother Vern remembers all of the ducks they tended and eating ducks eggs.

At home, everyone spoke German, not English. Frank Langenhorst, although born in the United States in the late 1800s insisted the children speak German.

“We learned English in school,” Joe said, so by third grade they could speak it “pretty well,” but not at home.

The Langenhorst men did their duty and all joined the service. When Herbie was drafted, he didn’t complain; he just went because it was his duty.

He had a sweetheart whom the family was sure he would marry when he came home, perhaps because he had bought ground to build a house before he left.

“He was strong,” Joe said of his younger brother, because farm work made him strong.

Beginning as a private, he carried a 30-caliber machine gun into the thick jungles of Vietnam.

And because the foliage was so thick, he told his family he’d shoot in the direction he thought the enemy was hiding, but it was too difficult to see anything. It was, after all, 1968, and equipment wasn’t so sophisticated.

His sister, Darlene, in high school at the time, received a letter from Herbie in 1968 telling the family he was now staying in one place, in Quang Tri Province, standing guard duty and was no longer tramping through the jungles where it was hard to receive letters from home.

Understandably, the family was relieved until the telegram dated Oct. 22 came. The Secretary of the Army expressed his regrets that Herbie had died Oct. 18 “of injuries received while standing on an aircraft landing zone when he was hit by flying debris from an aircraft which crashed and burned.”

Herbie had been standing on the landing strip when a helicopter crashed. He had served less than a year in Vietnam and had just celebrated his 22nd birthday.

Herbie received the Bronze Star posthumously (medal below), and Darlene has kept that medal, along with the others he received and buttons from his jacket, the letter from President Johnson and the

The family received more official telegrams as his body made its way back to Germantown.

Herbie’s father went to the funeral home to make sure the person they would bury was, indeed, his son. He made sure all of the other children saw their brother.

They said their mother was devastated, and Vern remembers talking to his father about Herbie’s death.

It was the only time he spoke of it to Vern.

A stoic man, he didn’t share his feelings easily or openly. He said he always wanted to be the first to go, Vern said his father told him.

In describing their brother, Darlene said “he was a very sweet boy; he would do anything for anybody.”

Brother Joe agreed. “He was one of the most giving persons you’d ever want to meet.”

When he saw others return from Vietnam, some who had been in areas sprayed with Agent Orange, Joe wondered if Herbie would return. In thinking about Herbie, Joe said next year it would be 50 years since he died. He still remembers the lack of respect for Vietnam veterans returning from the battlefield whether they walked off a plane or were carried off by their brothers in arms to be returned to their families.

This was a kind of turning point year for the war in Vietnam. The TET Offensive began at the end of January 1968.

It shocked the American public because at that time people thought the United States was winning the war.

It was the year 540,000 U.S. troops served in Vietnam; the year people saw a man suspected of being Viet Cong executed. A photographer and videographer captured the event and shared it with the American public.

It was the year of the My Lai massacre. It was the year Chicago saw anti-Vietnam War riots. And it was the year Cpl. Herbert Cyril Langenhorst died. Please remember all deceased veterans on Memorial Day.